by John Carey

What follows is an extract from John Carey’s introduction to The Faber Book of Reportage, 1987. Here he explains the distinction we have to think of between writing truth and writing fiction. When Carey refers to reportage he does so in the broad sense, meaning live, on-the-spot news journalism.

…if we ask what took the place of reportage in the ages before it was made available to its millions of consumers, the likeliest answer seems to be religion.

Not, of course, that we should assume pre-communication age man was deeply religious, in the main. There is plenty of evidence to suggest he was not. But religion was the permanent backdrop to his existence, as reportage is for his modern counterpart. Reportage supplies modern man with a constant and reassuring sense of events going on beyond his immediate horizon (reassuring even, or particularly, when the events themselves are terrible, since they then contrast more comfortingly with the reader’s supposed safety). Reportage provides modern man, too, with a release from his trivial routines, and a habitual daily illusion of communication with a reality greater than himself. In all these ways religion suggests itself as the likeliest substitute pre-modern man could have found for reportage, at any rate in the West.

When we view reportage as the natural successor to religion, it helps us to understand why it should be so profoundly taken up with the subject of death. Death, in its various forms of murder, massacre, accident, natural catastrophe, warfare, and so on, is the subject to which reportage naturally gravitates, and one difficulty, in compiling an anthology of this kind, is to stop it becoming just a string of slaughters. Religion has traditionally been mankind’s answer to death, allowing him to believe in various kinds of permanency which make his own extinction more tolerable, or even banish his fear of it altogether. The Christian belief in personal immortality is an obvious and extreme example of this. Reportage, taking religion’s place, endlessly feeds its reader with accounts of the deaths of other people, and therefore places him continually in the position of a survivor – one who has escaped the violent and terrible ends which, it graphically apprises him, others have come to. In this way reportage, like religion, gives the individual a comforting sense of his own immortality.

If reportage performs these social functions it clearly has a social value comparable to that which religion once had. Its ‘cultural’ value, on the other hand, has generally been considered negligible with certain favoured exceptions such as Mark Twain’s The Innocents Abroad, which are allowed to be literature because their authors also wrote respectable literary hooks. The question of whether reportage is ‘literature’ is not in itself interesting or even meaningful. ‘Literature’, we now realise, is not an objectively ascertainable category to which certain works naturally belong, but rather a term used by institutions and establishments and other culture-controlling groups to dignify those texts to which, for whatever reasons, they wish to attach value. The question worth asking therefore is not whether reportage is literature, hut why intellectuals and literary institutions have generally been so keen to deny it that status.

Resentment of the masses, who are regarded as reportage’s audience, is plainly a factor in the development of this prejudice. The terms used to express it are often social in their implications. ‘High’ culture is distinguished from the ‘vulgarity’ said to characterize reportage. But the disparagement of reportage also reflects a wish to promote the imaginary above the real. Works of imagination are, it is maintained, inherently superior, and have a spiritual value absent from ‘journalism’. The creative artist is in touch with truths higher than the actual, which give him exclusive entry into the soul of man.

Such convictions seem to represent a residue of magical thinking. The recourse to images of ascent which their adherents manifest, the emphasis on purity, the recoil from earthly contamination, and the tendency towards a belief in inspiration, all belong to the traditional ambience of priesthoods and mystery cults. Those who hold such views about literature are likely, also, to resent critical attempts to relate authors’ works to their lives. The biographical approach, it is argued, debases literature by tying it to mere reality: we should release texts from their authors, and contemplate them pure and disembodied, or at any rate only in the company of other equally pure and disembodied texts.

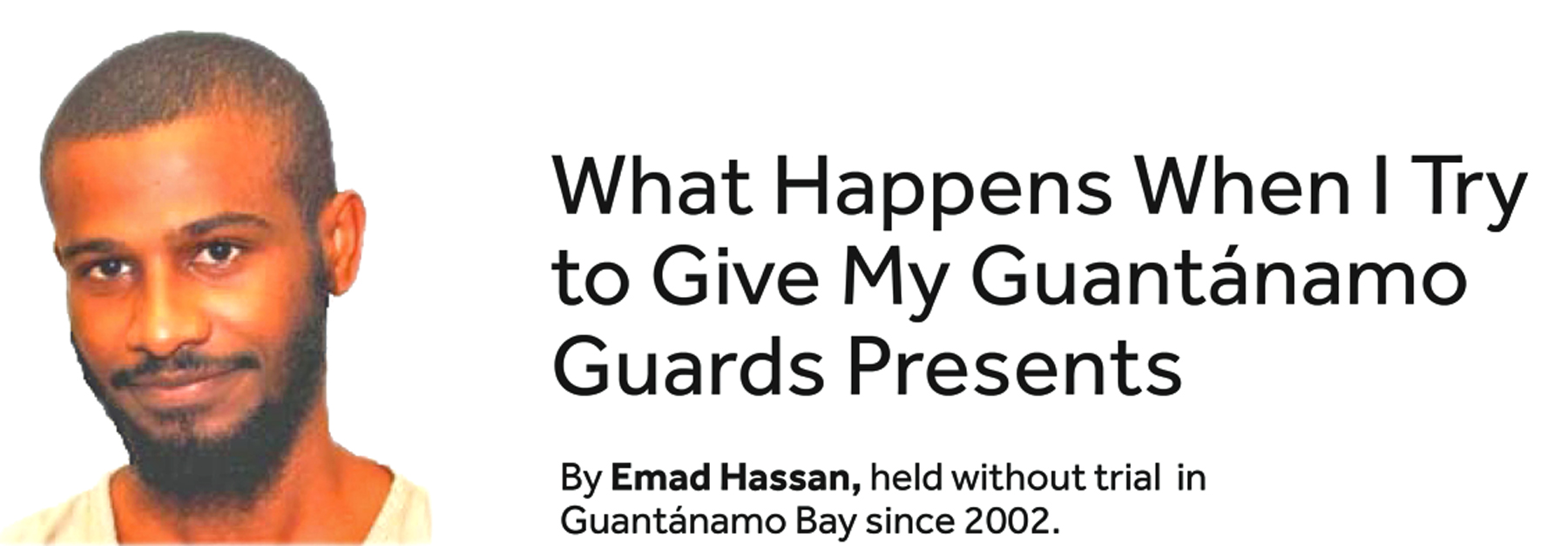

The superstitions that lie behind such dictates are interesting as primitive cultural vestiges, but it would be wrong to grant them serious attention as arguments. The advantages of reportage over imaginative literature, are, on the other hand, clear. Imaginative literature habitually depends for its effect on a ‘willing suspension of disbelief’ in audience or reader, and this necessarily entails an element of game or collusion or self-deception. Reportage, by contrast, lays claim directly to the power of the real, which imaginative literature can approach only through make-believe.

It would be foolish, of course, to belittle imaginative literature on this score. The fact that it is not real – that its griefs, loves and deaths are all a pretence, is one reason why it can sustain us. It is a dream from which we can awake when we wish, and so it gives us, among the obstinate urgencies of real life, a precious illusion of freedom. It allows us to use for pleasure passions and sympathies (anger, fear, pity, etc.), which in normal circumstances would arise only in situations of pain or distress. In this way it frees and extends our emotional life. It seems probable that much – or most – reportage is read as if it were fiction by a majority of its readers. Its panics and disasters do not affect them as real, but as belonging to a shadow world distinct from their own concerns, and without their pressing actuality. Because of this, reportage has been able to take the place of imaginative literature in the lives of most people. They read newspapers rather than books, and newspapers which might just as well be fictional.

However enjoyable this is, it represents, of course, a flight from the real, as does imaginative literature, and good reportage is designed to make that flight impossible. It exiles us from fiction into the sharp terrain of truth. All the great realistic novelists of the nineteenth century – Balzac, Dickens, Tolstoy, Zola – drew on the techniques of reportage, and even built eye-witness accounts and newspaper stories into their fictions, so as to give them heightened realism. But the goal they struggled towards always lay beyond their reach. They could produce, at best, only imitation reportage, lacking the absolutely vital ingredient of reportage, which is the simple fact that the reader knows all this actually happened.

When we read (to choose the most glaring example) accounts of the Holocaust by survivors and onlookers, some of which I have included in this book, we cannot comfort ourselves (as we can when distressed by accounts of suffering in realistic novels) by reminding ourselves that they are, after all, just stories. The facts presumed demand our recognition, and require us to respond, though we do not know how to. We read the details – the Jews by the mass grave waiting to be shot; the father comforting his son and pointing to the sky; the grandmother amusing the baby – and we are possessed by our own inadequacy, by a ridiculous desire to help, by pity which is unappeasable and useless.

Or not quite useless, perhaps. For at this level (so one would like to hope) reportage may change its readers, may educate their sympathies, may extend – in both directions – their ideas about what it is to be a human being, may limit their capacity for the inhuman. These gains have traditionally been claimed for imaginative literature. Bur since reportage, unlike literature, lifts the screen from reality, its lessons are – and ought to be – more telling; and since it reaches millions untouched by literature, it has an incalculably greater potential.