This story is so graphically detailed it will make you squirm. It’s included because it’s so simply and courageously told. And though you may wriggle, writhe, weep and wonder, it might touch you powerfully too.

by Fanny Burney

Frances (Fanny) Burney was an admired friend of Dr Samuel Johnson. She served five years at the court of George III and Queen Charlotte as Second Keeper of the Royal Robes (1786-1791). Fanny Burney married Alexandre d’Arblay in 1793 after he had fled to England to escape the Revolution. They lived for ten years in France, from 1802-1812.

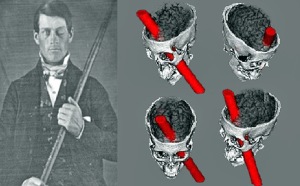

This rare patient narrative describes a mastectomy performed before the introduction of anesthesia. Madame d’Arblay first felt pain in her breast in August 1810. Cancer was diagnosed and Baron Larrey, Napoleon’s surgeon, agreed to perform the operation. To spare her suspense, she was given very little notice. The ‘M. d’A’ of her account is her husband. Alexander is her son.

Before the operation M. d’Arblay arranged for linen and bandages as his wife made her will and wrote farewell letters to him and her son. Her doctor gave her a wine cordial, the only anesthetic she received. Waiting for all the doctors to arrive must have been agony. The image of Fanny Burney is from a 1772 painting by Edward Francisco Burney.

One morning – the last of September, 1811, while I was in Bed & M. d’ A. was arranging some papers for his office, I received a letter written by M. de Lally to a Journalist, in vindication of the honoured memory of his Father against the assertions of Mme Deffand. I read it aloud to My Alexanders, with tears of admiration & sympathy, & then sent it by Alex: to its excellent Author, as I had promised the preceding evening. I then dressed, aided, as usual for many months, by my maid, my right arm being condemned to total inaction; but not yet was the grand business over, when another Letter was delivered to me – another. indeed! – ‘twas from M. Larrey, to acquaint me that at 10 o’clock he should be with me, properly accompanied, & to exhort me to rely as much upon his sensibility & his prudence, as upon his dexterity & his experience; he charged to secure the absence of M. d’ A: & told me that the young Physician who would deliver me his announce would prepare for the operation, in which he must lend his aid: & also that it had been the decision of the consultation to allow me but two hours’ notice. – Judge, my Esther, if I read this unmoved! – yet I had to disguise my sensations & intentions from M. d’ A! – Dr Aumont, the Messenger & terrible Herald, was in waiting; M. d’ A stood by my bedside; I affected to be long reading the Note, to gain time for forming some plan, & such was my terror of involving M. d’A. in the unavailing wretchedness of witnessing what I must go through, that it conquered every other, & gave me the force to act as if I were directing some third person. The detail would be too Wordy, as James says, but the wholesale is – I called Alex to my Bedside, & sent him to inform M. Barbier Neuville, chef du division du Bureau de M. d’A. that the moment was come, & I entreated him to write a summons upon urgent business for M. d’A. & to detain him till all should be over. Speechless & appalled, off went Alex, &, as I have since heard, was forced to sit down & sob in executing his commission. I then, by the maid, sent word to the young Dr Aumont that I could not be ready till one o’clock: & I finished my breakfast, & – not with much appetite, you will believe! forced down a crust of bread, & hurried off, under various pretences, M. d’ A. He was scarcely gone, when M Du Bois arrived: I renewed my request for one o’clock: the rest came; all were fain to consent to the delay, for I had an apartment to prepare for my banished Mate. This arrangement, & those for myself, occupied me completely. Two engaged nurses were out of the way – I had a bed, Curtains, & heaven knows what to prepare – but business was good for my nerves. I was obliged to quit my room to have it put in order: – Dr Aumont would not leave the house; he remained in the Sallon, folding linen! – He had demanded 4 or 5 old & fine left off under Garments – I glided to our Book Cabinet: sundry necessary works & orders filled up my time entirely till One o’dock, When all was ready – but Dr Moreau then arrived, with news that M. Dubois could not attend till three. Dr Aumont went away – & the Coast was clear. This, indeed, was a dreadful interval. I had no longer anything to do – I had only to think – TWO HOURS thus spent seemed never-ending. I would fain have written to my dearest Father – to You, my Esther – to Charlotte James – Charles – Amelia Lock – but my arm prohibited me: I strolled to the Sallon – I saw it fitted with preparations, & I recoiled – But I soon returned; to what effect disguise from myself what I must so soon know? – yet the sight of the immense quantity of bandages, compresses, spunges, Lint – made me a little sick: – I walked backwards & forwards till I quieted all emotion, & became, by degrees, nearly stupid – torpid, without sentiment or consciousness; – & thus I remained till the Clock struck three. A sudden spirit of exertion then returned, – I defied my poor arm, no longer worth sparing, & took my long banished pen to write a few words to M. d’ A – & a few more for Alex, in case of a fatal result. These short billets I could only deposit safely, when the Cabriolets – one – two – three – four – succeeded rapidly to each other in stopping at the door. Dr Moreau instantly entered my room, to see if I were alive. He gave me a wine cordial, & went to the Sallon. I rang for my Maid & Nurses, – but before I could speak to them, my room, without previous message, was entered by 7 Men in black, Dr Larry, M. Dubois, Dr Moreau, Dr Aumont, Dr Ribe, & a pupil of Dr Larry, & another of M. Dubois. I was now awakened from my stupor – & by a sort of indignation – Why so many? & without leave? – But I could not utter a syllable. M. Dubois acted as Commander in Chief. Dr Larry kept out of sight; M. Dubois ordered a Bed stead into the middle of the room. Astonished, I turned to Dr Larry, who had promised that an Arm Chair would suffice; but he hung his head, & would not look at me. Two old mattrasses M. Dubois then demanded, & an old Sheet. I now began to tremble violently, more with distaste & horror of the preparations even than of the pain. These arranged to his liking, he desired me to mount the Bed stead. I stood suspended, for a moment, whether I should not abruptly escape – I looked at the door, the windows – I felt desperate – but it was only for a moment, my reason then took the command, & my fears & feelings struggled vainly against it. I called to my maid – she was crying, & the two Nurses stood transfixed at the door. Let those women all go! cried M. Dubois. This order recovered me my Voice – No, I cried, let them stay! qu’elles restent! This occasioned a little dispute, that re-animated me – The maid, however & one of the nurses ran off – I charged the other to approach, & she obeyed. M. Dubois now tried to issue his commands en militaire, but I resisted all that were resistable – I was compelled, however, to submit to taking off my long robe de Chambre, which I had meant to retain – Ah, then, how did I think of my Sisters! – not one, at so dreadful an instant, at hand, to protect – adjust – guard me _ I regretted that I had refused Mlle de Maisonneuve – Mlle Chastel _ no one upon whom I could rely – my departed Angel! _ how did I think of her! – how did I long -long for my Esther _ my Charlotte! – My distress was, I suppose, apparent, though not my Wishes, for M. Dubois himself now softened, & spoke soothingly. Can You, I cried, feel for an operation that, to You, must seem so trivial? _ Trivial? he repeated – taking up a bit of paper, which he tore unconsciously, into a million of pieces, oui – c’est peu de chose, mais – ‘ he stammered, & could not go on. No one else attempted to speak, but I was softened myself, when I saw even M. Dubois grow agitated, while Dr Larry kept always aloof, yet a glance showed me he was pale as ashes. I knew not, positively, then, the immediate danger, but every thing convinced me danger was hovering about me, & that this experiment could alone save me from its jaws. I mounted, therefore, unbidden, the Bed stead & M. Dubois placed me upon the mattress. & spread a cambric handkerchief upon my face. It was transparent, however, & I saw, through it, that the Bed stead was instantly surrounded by the 7 men & my nurse. I refused to be held; but when, Bright through the cambric, I saw the glitter of polished Steel – I closed my Eyes. I would not trust to convulsive fear the sight of the terrible incision. A silence the most profound ensued, which lasted for some minutes, during which, I imagine, they took their orders by signs, so made their examination – Oh what a horrible suspension! – I did not breathe – & M. Dubois tried vainly to find any pulse. This pause, at length, was broken by Dr Larry, who, in a voice of solemn melancholy, said ‘Qui me tiendra ce sein? -’ .

No one answered; at least not verbally; but this aroused me from my passively submissive state, for I feared they imagined the whole breast infected – feared it too justly, – for, again through the Cambric, I saw the hand of M. Dubois held up, while his forefinger first described a straight line from top to bottom of the breast, secondly a Cross, & thirdly a Circle; intimating that the WHOLE was to be taken off. Excited by this idea, I started up, threw off my veil, &, in answer to the demand ‘Qui me tiendra ce sein?’ cried ‘C’est moi, Monsieur!’ & I held my hand under it, & explained the nature of my sufferings, which all sprang from one point, though they darted into every part. I was heard attentively, but in utter silence, & M. Dubois then replaced me as before, &, as before, spread my veil over my face. How vain. alas, my representation! immediately again I saw the fatal finger describe the Cross – & the circle _ Hopeless, then, desperate, & self-given up, I closed once more my Eyes, relinquishing all watching, all resistance, and interference, & sadly resolute to be wholly resigned.

My dearest Esther, – & all my dears to whom she communicated this doleful ditty, will rejoice to hear that this resolution once taken. was firmly adhered to, in defiance of a terror that surpasses description, & the most torturing pain. Yet – when the dreadful steel was plunged into the breast – cutting through veins – arteries – flesh – nerves – I needed no injunctions not to restrain my cries, – began a scream that lasted unintermittingly during the whole time of the incision & I almost marvel that it rings not in my Ears still, so excruciating was the agony. When the wound was made, & the instrument was withdrawn, the pain seemed undiminished, for the air that suddenly rushed into those delicate parts felt like a mass of minute but sharp & forked poniards, that were tearing the edges of the wound – but when again I felt the instrument – describing a curve, cutting against the grain, if I may so say, while the flesh resisted in a manner so forcible as to oppose & tire the hand of the operator, who was forced to change from the right to the left – then, indeed, I thought I must have expired. I attempted no more to open my Eyes – they felt as if hermetically shut, & so firmly closed that the Eyelids seemed indented into the Cheeks. The instrument this second time withdrawn, I concluded the operation over – Oh no! presently the terrible cutting was renewed – & worse than ever, to separate the bottom, the foundation of this dreadful gland, the parts to which it adhered – Again all description would be baffled – yet again all was not over, – Dr Larry rested but his own hand & – Oh Heaven! – I then felt the Knife rackling against the breast bone – scraping it! – This performed, while I yet remained in utterly speechless torture, I heard the Voice of Mr Larry, – (all others guarded a dead silence) in a tone nearly tragic, desire everyone present to pronounce if anything more remained to, be done; The general voice was Yes, – but the finger of Mr Dubois – which I literally felt elevated over the wound, though I saw nothing, & though he touched nothing, so indescribably sensitive was the spot – pointed to some further requisition – & again began the scraping! – and, after this, Dr Moreau thought he discerned a peccant attom – and still, & still, M. Dubois demanded attom after attom – My dearest Esther, not for days, not for Weeks, but for Months I could not speak of this terrible business without nearly again going through it! I could not think of it with impunity! I was sick, I was disordered by a single question – even now, 9 months after it is over, I have a headache from going on with the account! & this miserable account, which I began 3 Months ago, at least, I dare not revise, nor read, the recollection is still so painful.

To conclude, the evil was so profound, the case so delicate, & the precautions necessary for preventing a return so numerous, that the operation, including the treatment & the dressing, lasted 20 minutes! a time, for sufferings so acute, that was hardly supportable – However, I bore it with all the courage I could exert, & never moved, nor stopt them, nor resisted, nor remonstrated, nor spoke except once or twice, during the dressings, to say ‘Ah Messieurs! que je vous plains! -’ for indeed I was sensible to the feeling concern with which they all saw what I endured, though my speech was principally – very principally meant for Dr Larry. Except this, I uttered not a syllable, save, when so often they recommended, calling out ‘Avertissez moi, Messieurs! avertissez moi!’ Twice, I believe, I fainted; at least, I have two total chasms in my memory of this transaction, that impede my tying together what passed. When all was done, & they lifted me up that I might be put to bed, my strength was so totally annihilated, that I was obliged to be carried, & could not even sustain my hands & arms, which hung as if I had been lifeless; while my face, as the Nurse has told me, was utterly colourless. This removal made me open my Eyes – & I then saw my good Dr Larry, pale nearly as myself, his face streaked with blood & its expression depicting grief, apprehension, & almost horror.’

When I was in bed, – my poor M. d’Arblay – who ought to write you himself his own history of this Morning – was called to me – & afterwards our Alex.