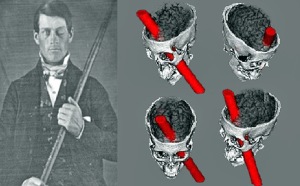

Phineas Gage, above, was clearing rocks for the US railroad in 1848 when dynamite he’d just placed in a hole was accidentally fired. The heavy metal pole he’s seen holding rocketed through his skull leaving a two-inch tunnel diagonally through his head, tearing away his pre-frontal lobe. Amazingly he not only lived, he sat up beside the buggy driver who took him to the nearest doctor, chatting away. Despite the severity and extent of his injuries he seemed to make an almost complete physical recovery, though it was soon evident that mentally he had changed, significantly. More than 100 years passed before scientists realised that Phineas Gage had been living proof that brain and mind are connected but are not single separate entities. Instead they’re made of several different compartments all with distinct and separate functions.

Or, so it seemed. But nothing to do with the brain is ever simple . Or uncontroversial.

That summer Mr Phineas Gage was a young man of 25 years, a popular gang boss working on the Rutland and Burlington railway of Boston. He was fit, energetic, strong, a model employee, a pillar of his community. Then he suffered an accident so traumatic it is a miracle he survived yet he survived almost unchanged. Almost, but not quite.

Phineas Gage’s survival was a boon to what was the then unknown, barely even nascent science of neurology. From Mr Gage scientists learned perhaps their single most important insight ever into the workings of the human brain.

At the time of the accident the railroad faced a stubborn outcrop of rock blocking its planned path. Mr Gage’s job was to break these rocks with strategically placed explosives. In this task he employed a straight cylindrical metal pole three and a half feet in length, one and one half inches thick, ground to a needle-sharp point and weighing 13 and a half pounds. With this implement in hand Mr Gage would first make a deep hole, fill it one third with gunpowder, attach a fuse, top this with sand, damping down the sand to form a tight seal. Then, from a safe distance, he and his assistant would light the fuse to detonate the charge and clear the rock.

On the day in question Mr Gage was going about his business when his attention was distracted by a call from behind. He failed to realise that the sand had not been applied and began damping down heavily onto the exposed gunpowder with his metal bar. This created a spark that ignited the powder causing a large explosion. The metal bar, his damping iron, rocketed skyward with the force of an exploding missile.

Between this rocketing metal spear and the freedom of the sky there stood Phineas Gage. Upon exiting its silo the missile missed his body but entered his jawbone just left of his chin. Without slowing it rocketed upwards though his brain, blasting away the prefrontal lobe to exit through a two inch gaping, mushroom-shaped hole at the top of his skull. The metal spear landed some 50 feet from the scene. Phineas Gage was knocked clean off his feet and assumed by all watching to be instantly killed. Not so. Incredibly he rose mere seconds after the explosion and walked unaided to a nearby bench, shaken, bleeding but seemingly otherwise little the worse. All including Gage himself at first assumed that the missile had hit him only a glancing blow.

This was not so, though even when the scale of injury was realized Gage refused to lie down. A coach and pair came to convey him four miles to the local doctor. He sat upright beside the driver the entire way.

The local doctor, James Harlow, promptly examined the patient and found a remarkable clear, clean wound. ‘The patient’, Dr Harlow later wrote, ‘bore his sufferings with the most heroic firmness. He recognized me at once, and said he hoped he was not much hurt. He seemed to be perfectly conscious, but was getting exhausted from the hemorrhage. His person, and the bed on which he was laid, were literally one gore of blood.’

Gage appeared normal, speaking and behaving merely as if slightly shaken, though he had a near perfect two inch hole right through his head from below his chin to the top of his skull. Yet he seemed coherent, alert and in little pain. Harlow’s assistant Dr Williams wrote later that he could see the man’s brain pulsating clearly through the gaping, funnel-shaped hole in his skull. Gage talked all the time while Williams was examining him. Crude chemical disinfection was recognized as important even then and the wound was vigorously if rather roughly cleaned. Gage later suffered from abscesses, but survived not just that day, but for 13 more years.’

The point of such a bizarre tale is simple. What Phileas Gage had shown was that the mind has many distinct compartments each responsible for different parts of what, collectively, adds up to our mind, to ‘us’.

Phineas Gage was healed and appeared unchanged. Physically, remarkably, he was. He rapidly regained outward health and strength. Save for losing the sight in his left eye he could touch, see and hear as before. His sense of smell was unchanged. He could walk purposefully upright, use his hands dexterously as before yet those who knew him noticed powerful, seemingly permanent change to his character and personality.

Dr Harlow described him as follows. ‘The intellectual balance between his human faculties and animal propensities has been destroyed.’ Gage started to swear foul oaths and gross profanities, something foreign to him before the accident. He became irreverent, irritable, inconstant, a drunkard and a brawler. Women were counselled to avoid his company for fear of offence or worse. Indeed so radical was the change in personality that people who had known him before could scarcely recognise the man. It became clear: Phineas Gage was no longer Phineas Gage.

Though intensely documented, the real lessons from the strange case of Phineas Gage were not realised for 100 years, before it was appreciated that Gage’s experience shows that by altering or removing a small and specific portion of the brain, the mind can be so changed as to alter someone’s personality out of all recognition. Phineas Gage’s accident shows us that the human mind in its home the brain has many compartments and that damage in one area need not noticeably affect all or even any of the other areas.

Recently though this version of Mr Gage’s story has been challenged. Two photographs of Gage and a physician’s report of his physical and mental condition late in life were published in 2009 and 2010, detailing new evidence that suggests Gage’s most serious mental changes may have been temporary, so that in later life he was far more functional, and socially far better adjusted, than was previously assumed.

Perhaps, over time, his brain regained some of its former functions. It is of course a remarkable thing, the human brain. However, a noted psychologist has commented, ‘Phineas’s story is [primarily] worth remembering because it illustrates how easily a small stock of facts becomes transformed into popular and scientific myth.’

It’s a good story though. And true, for sure.