It was cold and my feet hurt. I’d just been rejected, for the umpteenth time and been politely told off by a station guard for rattling my bucket. ‘It annoys the staff,’ he explained. ‘Well, if you do it too much it does.’ Then a dignified middle-aged man with a beard trailing his family behind him stepped from the throng that was flowing from the shopping centre and stopped, right in front of me. He looked me full in the eye as he dug inside his voluminous winter coat, pulled out his pocket book and proceeded to empty its contents into my bucket. My spirits soared. Then he gathered his family around him, mother, teenage son and two younger daughters and spoke to them for a while in a language I couldn’t catch. Soon they were all rummaging among their clothing. The procedure took some time. Then the teenage son, beaming from ear to ear, came over to pour handfuls more cash into my bucket.

‘Thank you’, he said, then bounced off with a spring in his step to catch his departing family. For the first time that day, I felt great.

I was with my wife, Marie, and younger son, Charlie, standing at the top of the escalators in Bond Street station, just outside the barriers. It was Easter Sunday and, though a lot thinner than we’d anticipated, a constant flow of shoppers was coming through. Marie and I each had a bucket, Charlie had two and we’d a three-hour stint to complete. We were collecting money for Syria’s refugees and those displaced by civil war inside the country, three million-plus and growing by the day.

That sea of faces rising from the escalators is daunting, first time you confront it. They come in surges, a mixed amorphous mass. The last thing they’re expecting to greet them is three white Brits in a line, rattling buckets. Not all are pleased. Most are indifferent. Some are, well, extraordinary. If only we could have an announcement at the foot of the escalator, saying, ‘Get your money ready!’

Bond Street station is the world in microcosm, a mini United Nations. In our three hours it seemed as if every conceivable ethnic grouping filed past us. We couldn’t help but notice which were the more generous. It wasn’t the white British middle classes, far from it. Charlie felt South Asians gave most to him – a Japanese woman with a huge smile gave him half the contents of her purse. A Chinese woman with a cheeky grin slipped me a tenner. But it was middle-eastern people, mainly Muslims, who put most in my bucket. Marie’s too.

Young couples are the least generous, or so it seemed to us, with older couples not far behind. Some people love givers and giving, so support us with looks. Others prefer to look away.

Three people come at me from different angles all at the same time. Briefly the bucket gets busy. I don’t know who to thank first, so I thank the whole foyer, loudly. The station manager beams. Everyone is looking at me now.

Then there’s a lull. Busyness comes and goes, but the shoppers are few and I fear it’s not enough. We’re doing badly. Someone tells us that most shops are closed. For a full 20 minutes everyone ignores us. Then Marie says, ‘I’ve got three tenners.’ I think of Pavarotti and Co. but resist breaking into song.

Smile. Make eye contact. The brightest eyes are the most generous, there’s no doubting that. The bucket feels heavier, but isn’t really. We stand stock still, not rattling, not moving, buckets aloft. Then, in unison, we give them a sway.

Children really enjoy giving. A man stood in front of me for several minutes digging in his pockets. Then, having found his oyster card, he left without giving. Behind him a gaggle of Syrian women, hands ornate with henna designs, ask if they can take my photo, then give me a pile of cash. ‘Here’s £10.00, says another woman, ‘Have a nice day and thank you very much for what you’re doing.’ Smarter-dressed people are not more generous. Expensive coats don’t give, we reckon.

A young Turkish boy maybe eight or nine asks me what I’m doing.‘Why are they fighting?’, he asks. ‘What’s a refugee?’ I try to explain but can’t give him a decent justification. ‘It’s just bad’, I say. ‘People have to leave their homes and loved ones in the middle of the night.’

He looks about to get emotional. ‘I’ll speak to my auntie, ‘ he promises, ‘and come back.’ He didn’t, though he tried, I’m sure. And used some of my lines too, I bet. Perhaps, as he grows, he’ll think about it…

A young Italian man asks me the way to Buckingham Palace. I oblige, though he gives me nothing but a smile. Then another chap asks me why I’m doing this. I should have quoted some lines from A A Gill in today’s Sunday Times, but I didn’t bring it with me.

As I watch, figures appear out of the darkness, bent double under sacks. Families hold hands, moving past us like heavy ghosts. This is the last leg of one of the most dangerous journeys on Earth.

Gill goes on, in similar, graphic vein. Note for next collection: bring a supply of moving emotional stories, because sometimes people want to talk. ‘Why isn’t there more on the News?,’ one man asks. Marie responds accurately. ‘I don’t know.’

Just as we were getting ready to go a woman in a headscarf walked up to Charlie and asked what he was doing. She was young, about 25, and crying, big tears running down her cheeks. As she left him to visit the cash machine in the corner of the concourse, her eyes met mine. Minutes later she was back, clutching money. She didn’t want to speak, just put two notes into my bucket, urgently. I watched till, with a gentle push from her, they were gone. Then so was she. I was overcome.

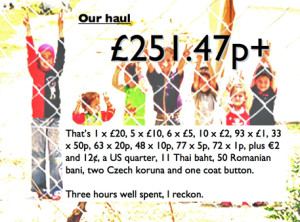

Our time was up. We thanked London Transport’s wonderful people, signed out then headed off to find a pub, thirsty and a bit tearful. As we sauntered down Brook Street a passing gent hailed Charlie. ‘For Syria’, he said, putting a fiver in Charlie’s bucket. For a minute I thought Charlie was going to say, ‘But we’ve finished for the day.’ He didn’t.

‘You’re a toff,’ he said, beaming.

Truly it’s never too late, to do something wonderful.

An abridged version of this article is featured on The Guardian’s website.

At the time of writing Ken Burnett was one of six independent trustees of the UK’s Disasters Emergency Committee, the unifying body for 14 leading British aid charities which come together in times of great need to raise money for the victims of crisis and disaster. To support the DEC go here.