by Sir Charles Sherrington

This is the finest description I’ve read of the wonder of life. It’s long, but oh-so worth it. I’ve included this extract in full because it’s a story everyone should read at least once, just to taste the sheer miraculousness of it. The English physiologist Sir Charles Sherrington (1857-1952) won a Nobel Prize in 1932 for his work on the nervous system of mammals. Experimenting on cats, dogs, monkeys and apes that had had their cerebral hemispheres removed, he showed that reflexes must be regarded as integrated activities of the whole organism. He coined the words ‘neuron’ and ‘synapse’ to mean the nerve cell and the point at which the nervous impulse is transmitted from one cell to another. His book Man and His Nature (1940) presents man – both mind and body – as the product of natural forces acting upon the materials of our planet. This extract is from the second edition, 1951.

Can then physics and chemistry out of themselves explain that a pin’s-head ball of cells in the course of so many weeks becomes a child? They more than hint that they can. A highly competent observer, after watching a motion-film photo-record taken with the microscope of a cell-mass in the process of making bone, writes: ‘Team-work by the cell-masses. Chalky spicules of bone-in-the-making shot across the screen, as if labourers were raising scaffold-poles. The scene suggested purposive behaviour by individual cells, and still more by colonies of cells arranged as tissues and organs.’[1] That impression of concerted endeavour comes, it is no exaggeration to say, with the force of a self-evident truth. The story of the making of the eye carries a like inference.

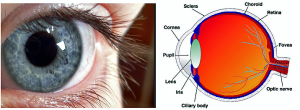

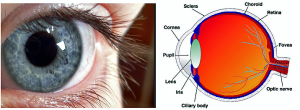

The eye’s parts are familiar even apart from technical knowledge and have evident fitness for their special uses. The likeness to an optical camera is plain beyond seeking. If a craftsman sought to construct an optical camera, let us say for photography, he would turn for his materials to wood and metal and glass. He would not expect to have to provide the actual motor power adjusting the focal length or the size of the aperture admitting light. He would leave the motor power out. If told to relinquish wood and metal and glass and to use instead some albumen, salt and water, he certainly would not proceed even to begin. Yet this is what that little pin’s-head bud of multiplying cells, the starting embryo, proceeds to do. And in a number of weeks it will have all ready. I call it a bud, but it is a system separate from that of its parent, although feeding itself on juices from its mother. And the eye it is going to make will be made out of those juices. Its whole self is at its setting out not one ten-thousandth part the size of the eye-ball it sets about to produce. Indeed it will make two eyeballs built and finished to one standard so that the mind can read their two pictures together as one. The magic in those juices goes by the chemical names, protein, sugar, fat, salts, water. Of them 80 per cent is water.

Water is the great menstruum of ‘life’. It makes life possible. It was part of the plot by which our planet engendered life. Every egg-cell is mostly water, and water is its first habitat. Water it turns to endless purposes; mechanical support and bed for its membranous sheets as they form and shape and fold. The early embryo is largely membranes. Here a particular piece grows fast because its cells do so. There it bulges or dips, to do this or that or simply to find room for itself. At some other centre of special activity the sheet will thicken. Again at some other place it will thin and form a hole. That is how the mouth, which at first leads nowhere, presently opens into the stomach. In the doing of all this, water is a main means.

Dragonfly’s eyes.

Dragonfly’s eyes.

The eye-ball is a little camera. Its smallness is part of its perfection. A spheroid camera. There are not many anatomical organs where exact shape counts for so much as with the eye. Light which will enter the eye will traverse a lens placed in the right position there. Will traverse; all this making of the eye which will see in the light is carried out in the dark. It is a preparing in darkness for use in light. The lens required is biconvex and to be shaped truly enough to focus its pencil of light at the particular distance of the sheet of photosensitive cells at the back, the retina. The biconvex lens is made of cells, like those of the skin but modified to be glass-clear. It is delicately slung with accurate centring across the path of the light which will in due time some months later enter the eye. In front of it a circular screen controls, like the iris-stop of a camera or microscope, the width of the beam and is adjustable, so that in a poor light more is taken for the image. In microscope, or photographic camera, this adjustment is made by the observer working the instrument. In the eye this adjustment is automatic, worked by the image itself!

The lens and screen cut the chamber of the eye into a front half and a back half, both filled with clear humour, practically water, kept under a certain pressure maintaining the eye-ball’s right shape. The front chamber is completed by a layer of skin specialised to be glass clear and free from blood-vessels which if present would with their blood throw shadows within the eye. This living glass-clear sheet is covered with a layer of tear-water constantly renewed. This tear-water has the special chemical power of killing germs which might inflame the eye. This glass-clear bit of skin has only one of the fourfold set of the skin-senses; its touch is always ‘pain’, for it should not be touched. The skin above and below this window grows into movable flaps, dry outside like ordinary skin, but moist inside so as to wipe the window clean every minute or so from any specks of dust, by painting over it fresh tear-water.

The light-sensitive screen at the back is the key-structure. It registers a continually changing picture. It receives, takes and records a moving picture life-long without change of ‘plate’, through every waking day. It signals its shifting exposures to the brain.

This camera also focuses itself automatically, according to the distance of the picture interesting it. It makes its lens ‘stronger’ or ‘weaker’ as required. This camera also turns itself in the direction of the view required. It is moreover contrived as though with forethought of self-preservation. Should danger threaten, in a moment its skin shutters close protecting its transparent window. And the whole structure, with its prescience and all its efficiency, is produced by and out of specks of granular slime arranging themselves as of their own accord in sheets and layers and acting seemingly on an agreed plan. That done, and their organ complete, they abide by what they have accomplished. They lapse into relative quietude and change no more. It all sounds an unskilful overstated tale which challenges belief. But to faithful observation so it is. There is more yet.

The little hollow bladder of the embryo-brain, narrowing itself at two points so as to be triple, thrusts from its foremost chamber to either side a hollow bud. This bud pushes toward the overlying skin. That skin, as though it knew and sympathized, then dips down forming a cuplike hollow to meet the hollow brain-stalk growing outward. They meet. The round end of the hollow brain-bud dimples inward and becomes a cup. Concurrently, the ingrowth from the skin nips itself free from its original skin. It rounds itself into a hollow ball, lying in the mouth of the brain-cup. Of this stalked cup, the optic cup, the stalk becomes in a few weeks a cable of a million nerve-fibres connecting the nerve-cells within the eye-ball itself with the brain. The optic cup, at first just a two-deep layer of somewhat simple-looking cells, multiplies its layers at the bottom of the cup where, when light enters the eye – which will not be for some weeks yet – the photo-image will in due course lie. There the layer becomes a fourfold layer of great complexity. It is strictly speaking a piece of the brain lying within the eye-ball. Indeed the whole brain itself, traced back to its embryonic beginning, is found to be all of a piece with the primordial skin – a primordial gesture as if to inculcate Aristotle’s maxim about sense and mind.

The deepest cells at the bottom of the cup become a photo-sensitive layer – the sensitive film of the camera. If light is to act on the retina – and it is from the retina that light’s visual effect is known to start – it must be absorbed there. In the retina a delicate purplish pigment absorbs incident light and is bleached by it, giving a light-picture. The photo-chemical effect generates nerve-currents running to the brain.

The nerve-lines connecting the photo-sensitive layer with the brain are not simple. They are in series of relays. It is the primitive cells of the optic cup, they and their progeny, which become in a few weeks these relays resembling a little brain, and each and all so shaped and connected as to transmit duly to the right points of the brain itself each light-picture momentarily formed and ‘taken’. On the sense-cell layer the ‘image’ has, picture-like, two dimensions. These space-relations ‘reappear’ in the mind; hence we may think their data in the picture are in some way preserved in the electrical patterning of the resultant disturbance in the brain. But reminding us that the step from electrical disturbance in the brain to the mental experience is the mystery it is, the mind adds the third dimension when interpreting the two dimensional picture! Also it adds colour; in short it makes a three dimensional visual scene out of an electrical disturbance.

All this the cells lining the primitive optic cup have, so to say, to bear in mind, when laying these lines down. They lay them down by becoming them themselves.

Cajal, the gifted Spanish neurologist, gave special study to the retina and its nerve- lines to the brain. He turned to the insect-eye thinking the nerve-lines there ‘in relative simplicity’ might display schematically, and therefore more readably, some general plan which Nature adopts when furnishing animal kind with sight. After studying it for two years this is what he wrote:

The complexity of the nerve-structures for vision is even in the insect something incredibly stupendous. From the insect’s faceted eye proceeds an inextricable criss-cross of excessively slender nerve-fibres. These then plunge into a cell-labyrinth which doubtless serves to integrate what comes from the retinal layers. Next follow a countless host of amacrine cells and with them again numberless centrifugal fibres. All these elements are moreover so small the highest powers of the modern microscope hardly avail for following them. The intricacy of the connexions defies description, before it the mind halts, abased. In tenuis labor. Peering through the microscope into this Lilliputian life one wonders whether what we disdainfully term ‘instinct’ (Bergson’s ‘intuition’) is not, as Jules Fabre claims, life’s crowning mental gift. Mind with instant and decisive action, the mind which in these tiny and ancient beings reached its blossom ages ago and earliest of all.

Fly’s eyes.

Fly’s eyes.

... The human eye has about 137 million separate ‘seeing’ elements spread out in the sheet of the retina. The number of nerve-lines leading from them to the brain gradually condenses down to little over a million. Each of these has in the brain, we must think, to find its right nerve-exchanges. Those nerve-exchanges lie far apart, and are but stations on the way to further stations. The whole crust of the brain is one thick tangled jungle of exchanges and of branching lines going thither and coming thence. As the eye’s cup develops into the nervous retina all this intricate orientation to locality is provided for by corresponding growth in the brain. To compass what is needed adjacent cells, although sister and sister, have to shape themselves quite differently the one from the other. Most become patterned filaments, set lengthwise in the general direction of the current of travel. But some thrust out arms laterally as if to embrace together whole cables of the conducting system.

Nervous ‘conduction’ is transmission of nervous signals, in this case to the brain. There is also another nervous process, which physiology was slower to discover. Activity at this or that point in the conducting system, where relays are introduced, can be decreased even to suppression. This lessening is called inhibition; it occurs in the retina as elsewhere. All this is arranged for by the developing eye-cup when preparing and carrying out its million-fold connections with the brain for the making of a seeing eye. Obviously there are almost illimitable opportunities for a false step. Such a false step need not count at the time because all that we have been considering is done months or weeks before the eye can be used. Time after time so perfectly is all performed that the infant eye is a good and fitting eye, and the mind soon is instructing itself and gathering knowledge through it. And the child’s eye is not only an eye true to the human type, but an eye with personal likeness to its individual parent’s. The many cells which made it have executed correctly a multitudinous dance engaging millions of performers in hundreds of sequences of particular different steps, differing for each performer according to his part. To picture the complexity and the precision beggars any imagery I have. But it may help us to think further.

There is too that other layer of those embryonic cells at the back of the eye. They act as the dead black lining of the camera; they with their black pigment kill any stray light which would blur the optical image. They can shift their pigment. In full daylight they screen, and at night they unscreen, as wanted, the special seeing elements which serve for seeing in dim light. These are the cells which manufacture the purple pigment, ‘visual purple’, which sensitizes the eye for seeing in low light.

Then there is that little ball of cells which migrated from the skin and thrust itself into the mouth of the eye-stalk from the brain. It makes a lens there; it changes into glass-clear fibres, grouped with geometrical truth, locking together by toothed edges. The pencil of light let through must come to a point at the right distance for the length of the eye-ball which is to be. Not only must the lens be glass-clear but its shape must be optically right, and its substance must have the right optical refractive index. That index is higher than that of anything else which transmits light in the body. Its two curved surfaces back and front must be truly centred on one and the right axis, and each of the sub-spherical curvatures must be curved to the right degree, so that, the refractive index being right, light is brought to a focus on the retina and gives there a shaped image. The optician obtains glass of the desired refractive index and skilfully grinds its curvatures in accordance with the mathematical formulae required. With the lens of the eye, a batch of granular skin-cells are told off to travel from the skin to which they strictly belong, to settle down in the mouth of the optic cup, to arrange themselves in a compact and suitable ball, to turn into transparent fibres, to assume the right refractive index, and to make themselves into a subsphere with two correct curvatures truly centred on a certain axis. Thus it is they make a lens of the right size, set in the right place, that is, at the right distance behind the transparent window of the eye in front and the sensitive seeing screen of the retina behind. In short they behave as if fairly possessed.

I would not give a wrong impression. The optical apparatus of the eye is not all turned out with a precision equal to that of a first-rate optical workshop. It has defects which disarm the envy of the optician. It is rather as though the planet, producing all this as it does, worked under limitations. Regarded as a planet which ‘would’, we yet find it no less a planet whose products lie open to criticism. On the other hand, in this very matter of the eye the process of its construction seems to seize opportunities offered by the peculiarity in some ways adverse of the material it is condemned to use. It extracts from the untoward situation practical advantages for its instrument which human craftsmanship could never in that way provide. Thus the cells composing the core of this living lens are denser than those at the edge. This corrects a focussing defect inherent in ordinary glass-lenses. Again, the lens of the eye, compassing what no glass-lens can, changes its curvature to focus near objects as well as distant when wanted for instance, when we read. An elastic capsule is spun over it and is arranged to be eased by a special muscle. Further, the pupil – the camera stop – is self-adjusting. All this without our having even to wish it; without even our knowing anything about it, beyond that we are seeing satisfactorily.

The making of this eye out of self-actuated specks which draw together and multiply and move as if obsessed with one desire namely to make the eye-ball. In a few weeks they have done so. Then, their madness over, they sit down and rest, satisfied to be life-long what they have made themselves, and, so to say, wait for death.

The chief wonder of all we have not touched on yet. Wonder of wonders, though familiar even to boredom. So much with us that we forget it all our time. The eye sends, as we saw, in to the cell-and-fibre forest of the brain throughout the waking day continual rhythmic streams of tiny, individually evanescent, electrical potentials. This throbbing streaming crowd of electrified shifting points in the spongework of the brain bears no obvious semblance in space-pattern, and even in temporal relation resembles but a little remotely the tiny two dimensional upside-down picture of the outside world which the eyeball paints on the beginnings of its nerve-fibres to the brain. But that little picture sets up an electrical storm. And that electrical storm so set up is one which affects a whole population of brain-cells, Electrical charges having in themselves not the faintest elements of the visual – having, for instance, nothing of ‘distance’, ‘right-side-upness”, nor ‘vertical’, nor ‘horizontal’, nor ‘colour’, nor ‘brightness’, nor ‘shadow’, nor ‘roundness’, nor ‘squareness”, nor contour’, nor ‘transparency’, nor ‘opacity’, nor ‘near’, nor ‘far’, nor visual anything – conjure up all these. A shower of little electrical leaks conjures up for me, when I look, the landscape; the castle on the height, or, when I look at him, my friend’s face, and how distant he is from me they tell me. Taking their word for it, I go forward and my other senses confirm that he is there.

It is a case of ‘the world is too much with us’; too banal to wonder at. Those other things we paused over, the building and shaping of the eye-ball, and the establishing of its nerve connections with the right points of the brain, all those other things and the rest pertaining to them we called in chemistry and physics and final causes to explain to us. And they did so, with promise of more help to come.

But this last, not the eye, but the ‘seeing’ by the brain behind the eye? Physics and chemistry there are silent to our every question. All they say to us is that the brain is theirs, that without the brain which is theirs the seeing is not. But as to how? They vouchsafe us not a word.

Source: Sir Charles Sherrington, Man on His Nature, 2nd edition, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1951. Taken from the Faber Book of Science, edited by John Carey.

[1] E.G.Drury, Psyche and the Physiologists and other Essays on Sensation (London 1938), p.4.